For several years, lovers have called for awareness of Asia: this is where some of the largest CO2 emitters reside. burn fossil fuels to tackle climate change.

Since late February, global energy prices have jumped because Russia invaded Ukraine. Countries in the region—including its three biggest economies China, Japan, and India—were criticized last year for not making a bigger commitment at the COP26 global climate change conference. But six months on, there is another, arguably more immediate reason for Asia to make the transition away from oil, gas, and coal: money.

The continent of Europe is attempting to lessen its reliance on natural gas from Russia by exploring the possibilities of using hydrogen as a replacement.

Japan, South Korea and China have invested heavily in hydrogen technology before the Ukraine war and the soaring cost of energy has provided an additional incentive to accelerate their transition to greener fuels. However, Asian economies have continued to burn coal to produce electricity despite how much it pollutes the environment. While some countries have made progress in moving away from fossil fuels, when China and India were hit by power shortages they turned to coal.

Japan began investing in nuclear power in the 1930s, but then in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, it went back to its original forms of energy.

Hydrogen can help countries make the transition from fossil fuels to renewables, say some experts. South Korea is betting on that technology, as it moves forward with efforts to develop hydrogen as an energy resource. The country has announced the largest government spending in Asia on developing hydrogen technology. Seoul is also investing in fuel cell power generation and hydrogen-powered vehicles.

Hydrogen is also considered by some experts in place to be the most practical alternative to fossil fuels, as it is able to be stored as a liquid, solid, or gas.

Hydrogen is a fuel that can be used either to generate electricity or as an energy source for fuel-cell vehicles. Unlike solar and wind power, it can be easily stockpiled and transported; however, there are different types of hydrogen and what South Korea is currently investing in is not emission-free.

The transition to ‘green hydrogen’

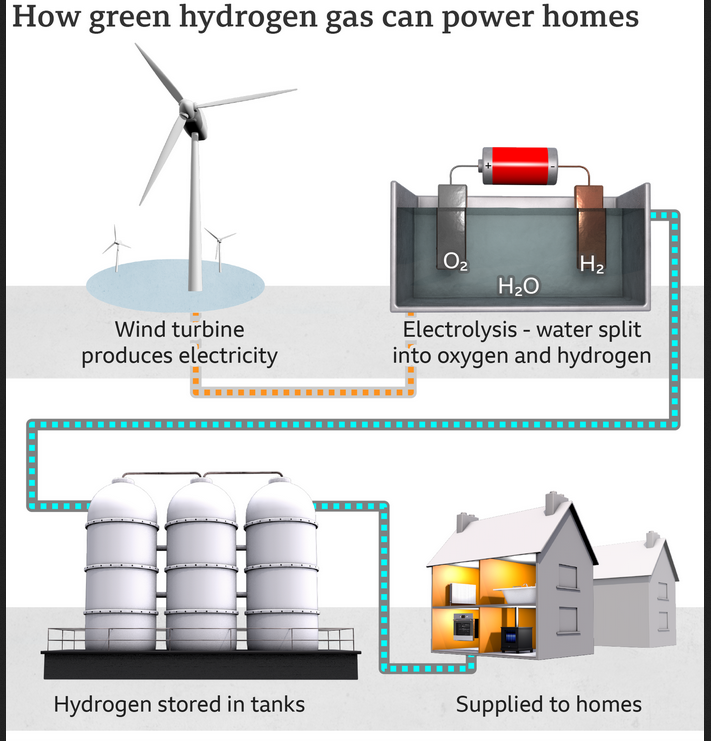

The goal is to eventually transition to so-called “green hydrogen”, which is also known as “clean hydrogen”.

Renewable energy sources, such as wind or solar power, are used to make hydrogen fuel, but it is the most expensive type of hydrogen to produce. This is why experts have seen fossil-fuel-based hydrogen production as a necessary first step toward green hydrogen.

South Korea’s hydrogen is created from natural gas, declared BloombergNEF’s lead hydrogen analyst Martin Tengler. It is referred to as “grey hydrogen.”

The next stage in the transition to renewable energy production is “blue hydrogen,” which is also made using fossil fuels but 60% to 90% of the carbon dioxide produced in the process is captured and stored. South Korea’s biggest natural gas supplier, SK, has invested 18 trillion won, or around ($15bn; £12bn), but only in grey and blue hydrogen. The boss of its hydrogen business unit, Hyeong-wook Choo, told the BBC that more technology and investment was needed to do so. With renewable sources of energy and infrastructure to capture and distribute it not readily available in much of Asia, a major challenge has been to develop the right mix of technologies to harness enough energy to mass produce hydrogen.

We can remove the production, production and distribution of hydrogen from our revitalisation efforts. When we achieve the goal of producing green hydrogen, commercial availability and further development will result.

The cost of producing green and grey hydrogen differs greatly. Green hydrogen costs more than two to three times grey hydrogen to produce, according to Mr Heo of S&P Global. Currently, it’s about $10 per kilogramme to produce green hydrogen. To be cost effective without government subsidies, the cost needs to decline by 70% to around $3 per kilogramme. But the jump in global energy prices means that “there’s clearly some momentum on green hydrogen because it is produced from renewable energy which is detached from the high fuel prices environment,” he added.

In European countries, the cost of making blue and red hydrogen, respectively, rose above 70%, after the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine, as assessed by energy consultancy Rystad Energy.

The availability of affordable green hydrogen could lead to a number of industries benefiting. The hydrogen could replace grey hydrogen in industries where there are no emissions-free alternatives, such as refining petroleum, producing fertiliser and heavy industries like steel production which require high temperatures. To be able to compete globally, South Korea has created a hydrogen alliance which more than a dozen companies have joined. “The hydrogen industry at the moment is like the solar industry about 20 years ago where there are few projects being developed and there is a big ambition in the market,” said Mr Heo.

One of the keys to South Korea’s green hydrogen ambitions is wind power. A consortium led by Korea Maritime and Ocean University is developing a floating offshore plant to produce green hydrogen in the city of Busan. “What we’re envisioning is to use electricity from wind and solar out at sea, to boil and electrolyse seawater to produce green hydrogen,” Doh Deog-hee, President of Korea Maritime and Ocean University said. It will be close to consumers, its advantage Heo said: “You can save the hydrogen transportation costs because that’s a big, very expensive part of the hydrogen value chain.”

However, hydrogen production from floating offshore wind farms cost more than $300 per megawatt hour compared to $100 per megawatt hour for producing electricity through solar power. How to optimise the cost of hydrogen production from such a facility is a profound question.

The switch to clean energy has always had costs. When global leaders met at COP26 in November, however, the world was facing higher fuel prices due to the pent-up demand after the pandemic lockdowns. For many countries it was and still is very tempting to go back to fossil fuels. The question is whether soaring fuel prices could be a bigger motivator for a change.